The History of Match Racing

It is the America’s Cup that is generally credited with the foundation of match racing, but it began a long time before that. There has been match racing as long as there has been sailing but, in the western world at least, one-on-one racing seems to have started in Holland in the 17th century and been brought to England by none other than King Charles II. Charles was a devoted and habitual sailor and, while living in exile in Bruges, he discovered the joys of yachting. The jaght (derived from the middle low German “jachtschiff” or hunting ship) was a fast sailing boat, largely used for the pursuit of pirates in shallow waters, but also for recreation, and they provided a welcome break for the impoverished king.

Greenwich to Gravesend (1600’s)

In 1660, the year of his restoration, Charles commissioned a new 100-ton yacht, Catherine, from Phineas Pitt, of Deptford. At the same time, James, Duke of York, took delivery of Anne, another 100-tonner, and the brothers raced from Greenwich to Gravesend and back for a purse of 100 guineas, with the Duke leading at the windward mark but the King overhauling him on the run home.

Racing on the Thames continued as an aristocratic pursuit over the next hundred years, and was formalised in 1775 by the Duke of Cumberland, brother of King George III, who formed the Cumberland Fleet. The Fleet’s first recorded race was held in July 1775, for a silver cup – the first Cumberland Cup – put up by the Duke.

Over the next seven years, the Cumberland Fleet held annual races for its members, who competed for further Cumberland Cups. In those days, these trophies were won outright and became the property of their winners and, while the original 1775 Cup was destroyed in a fire, the cups of 1776, 1777, 1780, 1781 and 1782 have over the years all been traced and recovered. They are now displayed in the entrance hall at 60 Knightsbridge, the present clubhouse in London of the Cumberland Fleet, now the Royal Thames Yacht Club.

In North America, the development of yacht racing was remarkably similar, finding its origins with the Dutch in New York in the 17th century and continuing unabated when the British took over. The first official yachting association was the Detroit Boat Club, founded in 1839, five years ahead of John C Stevens’ foundation of the New York Yacht Club. Match racing still flourishes at the Detroit Boat Club, where the one design of choice is the Flying Scot, designed in 1957 by Gordon K “Sandy” Douglass.

Match Racing in the USA

Although the America’s Cup is often cited as the archetype of match racing, the impression created by this is misleading. The basic tenet of match racing is the ‘level playing field’, resulting in the only difference between the competitors, as far as it is possible to ensure, being the human element, whether strategic, tactical or physical (but not numerical). Thus the boats being employed in a match should be complete one-designs; totally interchangeable. This, over the 160-year history of the America’s Cup, has only really been the case for a very brief period. The America’s Cup has always been a competition of deep pocketed owners attempting to design, build and sail a yacht that is capable of beating their competitor’s. Things have not always gone to plan however which has resulted in protracted legal disputes with sometimes acrimonious outcomes. The principle of one-design racing came about partly because of the search for a level playing field, but mostly because of the escalating expense of the existing ‘Class’ system, which was based on mathematical formulae. This allowed for design development and the frequent building of new boats, providing employment for designers, builders and sail-makers but also led to yachts being outclassed after a few seasons.

The first one-design was created by Thomas Middleton of the Shankill Corinthian Club, situated 10 miles south of Dublin, in 1887. The onedesigns he proposed, a class of double ended open dinghies of simple clinker-built pine construction with a lifting boiler plate, were know as Water Wags and can still be found racing in Dun Laoghaire, Co. Dublin.

The magnificent J’s (1930’s..)

If the lack of conformity was proving expensive for the dinghy sailor, then the America’s Cup was careering completely out of control; boats got bigger and bigger and more expensive. Looking at them now, it is hard to believe that the J-Class was introduced to the America’s Cup primarily because it was affordable – the rich didn’t want to look rich during the depression – but compared to the behemoths that would have appeared had they not been chosen in 1929, the Js were positively bargain basement yachts.

The Js campaigned until 1937, to be succeeded in 1958 (there was a 20 year hiatus in Cup activity during and after World War II) by the 12-metre Rule. These two classes of boats were more nearly identical than anything that had preceded them, but they constantly incorporated innovations that gave one team a major advantage – most famously with the winged keel of Australia II in 1983 – and the individual design of the boat was then the most significant factor in the America’s Cup.

Apart from two venerable competitions on the Great Lakes, the Richardson Trophy and the Canada Cup, prior to the 1960s, there was only one regular match-racing event on the yachting calendar, the King Edward VII Gold Cup, competed annually at the Royal Bermuda Yacht Club. It was given at the Tri- Centenary Regatta at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1907 by King Edward VII in commemoration of the 300th Anniversary of the first permanent settlement in America. C. Sherman Hoyt won the regatta and was the first to accept the now historic cup.

After three decades of holding the Cup, Mr. Hoyt gave it to the Royal Bermuda Yacht Club and proposed a regular one-on-one match race series in 6-metre yachts. In his letter he expressed the propriety of “my returning a British Royal trophy to the custody of your club, with its long record of clean sportsmanship and keenly contested races between your Bermuda yachts and ours of Long Island Sound, and elsewhere…”. The first winner of the Cup in its new format was the celebrated Briggs Cunningham, who was also the first skipper to win the America’s Cup in a 12-Metre. The club placed the Cup in competition in 1956 for match racing in yachts of the International One Design Class. Bert Darrell had the honour of being first to defend the Cup in this class and won it a total of six times. By winning his seventh championship in 2004, Russell Coutts surpassed Darrell to become the event’s all-time winner. In spite of the introduction of two new match racing regattas to join the Gold Cup, the Congressional Cup, at Long Beach, California in 1964 and the Royal Lymington Cup in the Solent in the following year, one-on-one boat racing, just like the America’s Cup, remained very much an elite sport. Racing was still the preserve of the established yacht clubs and the governing rules of racing precluded any intrusion by recent innovations such as television or the mood of the populace.

The three match racing competitions, Bermuda, Congressional and Lymington, survived through the ’70s, while similar events emerged across the world and, for the most part, died again. It became increasingly obvious that, as with every other sport, the age of the professional had arrived and, if match racing were to survive in a global environment, some radical changes needed to be made.

Professional Match Racing (1980’s..)

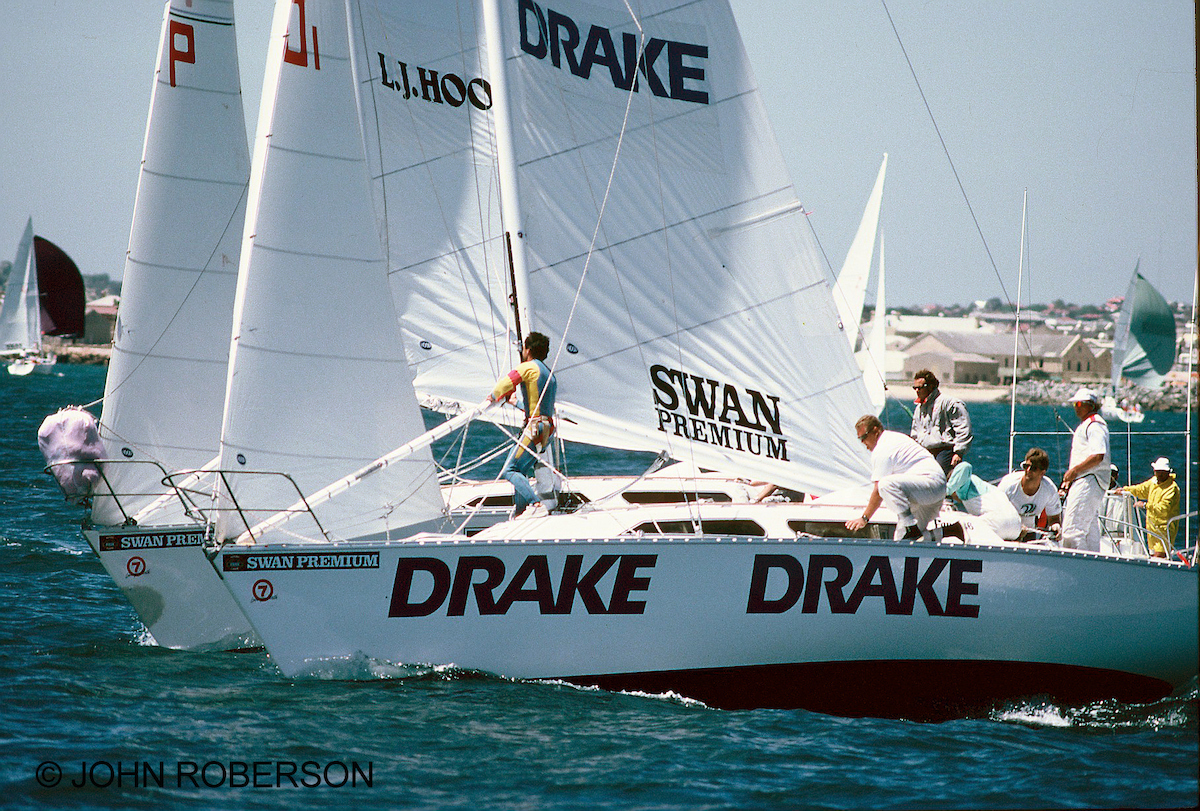

The public’s appetite was for instant sporting events with instant results, racing that was understandable and televisual. The America’s Cup in Fremantle in 1987, when whole nights were spent in the protest room, brought to a head the problem with the way sailing was still being run in a world where instant gratification was the norm. It was simply not good enough to have the facilities to broadcast the spectacle of live yachting and then to have to wait several hours for the result.

The idea of umpiring on the water, with instant protests and penalties, was tried out with success at a Maxi regatta in Newport Rhode Island later in 1987 and then adopted for the 1988 Congressional Cup, won by Peter Gilmour* – not only did the umpiring work, it added to the spectacle. The following year, the World Championship of Match Race Sailing at Lymington (won by Chris Dickson) used the same system (the term “Match Racing” was not yet formally used), and the International Yacht Racing Union (renamed ISAF in 1996) set up a classification system for match racing. And they were off! Now that the sport was comprehensible, the sponsors moved in and, now that the sport was sponsored, the stars began to emerge. Match racing moved the sailing hero into the public domain; from being an anonymous figure in a blazer, closeted in an exclusive yacht club, he became one of us. The World Match Racing Conference, created in 1985, moved sailing from the yacht club bar into the beer tent – sailing became ‘street’. In 1985, the average person would have heard of Dennis Conner and maybe John Bertrand, but hardly anyone else; now there was a whole new range of sailing celebrities about to enter the public consciousness.

The Match Racing World Championship, a single, rolling venue regatta until 2006, was first held in 1988, in Fremantle, and was won by Chris Dickson of New Zealand, who went on to win the next year in Lymington and in Bermuda in 1991. Australian Peter Gilmour won in 1990, ’97 and ’98 in New Zealand, Sweden and Japan and Kiwi Russell Coutts in Australia, the US and Croatia in ’92, ’93 and ’96. American Ed Baird triumphed in 1995 in Auckland, in 2003 in Italy and 2004 in Russia; Frenchman Bertrand Pacé, in 1994, Jesper Bank of Denmark, in 1999, Poland’s Karol Jablonski in 2002 and Australian James Spithill in 2005 were the other winners before the World Match Racing Tour took over.

Match racing received a tremendous fillip in 1995, when a sponsorship deal was brokered by Scott MacLeod, the eminence grise of the World Match Racing Association, with the cosmetics manufacturer Fabergé, under the title of Brut by Fabergé. Brut’s sponsorship ran for two years and comprised the match racing regattas at Bermuda, San Francisco, New York and Lymington, as well as the Brut Cup of France. Brut produced a cash prize of $250,000 for the overall winner, the highest prize yet awarded in any form of sailing, with a very lucrative ancillary prize pool to go with it. To win the big prize – and the ‘Fabergé Egg’ – a competitor had to win three of the five races; in 1997, Russell Coutts’ Team Magic won them all. Brut had raised the bar for the sport, but left it abruptly and in something of a state of limbo. The three years between Brut leaving and Swedish Match taking over represent something of the Dark Ages in World Match Racing, with the events continuing independently against a backdrop of internal disputes. By this time, product managers and venues had come to appreciate the efficacy of sponsoring and hosting events, giving birth to such occasions as the Hoya Royal Lymington Cup and the ACI Cup of Croatia, but the cohesion of the world tour was lost until 2000, when negotiations were completed with Swedish Match, who had been sponsoring the event in Sweden since 1996 and were just coming out of a Whitbread Round-the-World sponsorship.

“In 1998-99 we began creating the Swedish Match Tour,” says Scott MacLeod. “Swedish Match had been sponsoring the event in Marstrand since ’96 and had just finished the Whitbread. They were looking for something else; we were looking for a way to bring everybody back together and it needed to be structured in such a way that nobody could screw around with it, basically. “We wanted to keep it at nine or ten events and build up the quality. We wanted the top sailors who sowed the seed for the sponsorship, but always with room for the up-and coming guys to have a shot. This came from when we started Bermuda in 1989, when it was always about qualifiers and letting them have a shot at the big boys. “A lot of guys came through that system,” Scott goes on. “Ed Baird, Peter Holmberg. James Spithill – I remember James Spithill’s dad calling me up and saying could we get a spot for him in Bermuda. They obviously proved themselves once we got them in there.”

In addition to more than $800,000 in individual event prize money, the Swedish Match Tour awarded $200,000 to the top eight sailors on the Tour, with the first-place skipper netting $60,000. The Swedish Match Tour produced an annual 155 hours of television coverage reaching more than 426 million households worldwide.

In 2006, the Swedish Match Tour became the World Match Racing Tour, a cohesive, worldwide competition held at nine venues and incorporating a World Championship, sanctioned by ISAF.

Since its inception, WMRT has constantly been evolving and improving. In 2005, the inaugural Monsoon Cup, held in Kuala Terengganu, Malaysia, was the 50th event of the Swedish Match Tour and it has proceeded, over the next five years, to become the jewel in the crown of the World Match Racing Tour, being the culminating race of the year and carrying decisive points towards the Championship. Much of the credit for the creation of the Monsoon Cup goes to Malaysian Prime Minister at the time, Dato’ Seri Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, who decided, while on a fishing trip to Kuala Terengganu, that the monsoon season should be used as an advantage to the state and his people rather than being seen as a hurdle. The economic objectives included making the Monsoon Cup a catalyst for development in the state and creating economic opportunities in services and manufacturing sectors related to the event. Among them are hotels, tourism, restaurants, boat-building, food supplies, textiles and souvenirs. The Monsoon Cup turned the event venue, Pulau Duyong at the mouth of Terengganu River, from a sleepy fishing and boat-making village into modern and international class resort and marina.

The success of the Monsoon Cup, sailed in Foundation 36s, from Western Australia, led to the ignition of tremendous interest in match racing throughout Asia and the inauguration, in 2008, of a further WMRT event, the Korea Match Cup. Besides having a shoreside venue located in a brand-new marina complex 70 km south of Seoul on Korea’s west coast, the Korea Match Cup also invested in a fleet of new KM 36s built locally in Hwaseong City by Advanced Marine Tech. The boats were the first racing yacht to be built and sailed in Korea, with a match-race version produced for the Korea Match Cup event. Besides having a centreline retracting carbon bowsprit and asymmetric spinnakers, a unique feature of this match racing version is the addition of a cameraman’s cupola in the deck where there would usually be the main companionway: onboard cameramen are thus in a perfect position to capture the all the action up close.

At the opening ceremony for the 2010 event, together with the Korean International Boat Show, the governor of Gyeonggi province, said: “The ISAF World Match Racing Tour has inspired the people of Gyeonggi, it is one of Korea’s largest annual sporting events and is a powerful event for this region. It is rewarding to host such a high calibre set of sailors and will continue to create young talent for South Korea’s next generation of sailing sport enthusiasts.”